Everlasting Music – 2 – The The

OK. You’re 18 years old, first year at university. You find yourself wise and think you’ll change the world. You have only the future before you, and the future will bring you many things – or better: you’ll force the future to bring you them. I thought my friendships would last forever, my love – if the one and only appeared – would be eternal, my studies lead to more wisdom than I already carried in myself. Furthermore, I thought I would become the poet of my generation, I thought I was good at singing and was the only one feeling the world so deeply. Well… not everything came through (the singing sank away, the poet’s dreams found other ways of expression, I did not change the world yet).

But yes, I learned interesting things at university and would not want to miss it. And, at least some of my friendships still last – so does the one with my good friend who brought this stellar album by The The under my attention. Oh my, what a blast. Suddenly someone came around singing lines like

“In our lives we hunger for those we cannot touch

All the thoughts unuttered and all the feelings unexpressed

Play upon our hearts like the mist upon our breath”

or

“The more I see

The less I know

About all the things I thought were wrong or right

And carved in stone”

and all this with a sense of self-relativation, sustained by the passionate voice of Matt Johnson and the jangling guitar of Johnny Marr.

Even on a compact stereo I had back then – one of these that had “everything” in one piece: a cheap turntable with deplorable needle, an inconsistant tape deck, a digital (oh yes!) radio tuner, and a cd player that after some years did nothing but skip at the least particle of dust or fingerprint, all complemented with two small cardbox speakers the name unworthy. As I play the album now on my current and decent stereo setup, I hear so much more details and colors than I could have imagined at that time. But, nevertheless, a blast it was, that album. It still is.

In and Out

White, Red, Green and Blue

Concrete Beauty

Museum Insel Hombroich & Langen Foundation

At the start of the summer, I finally visited the Museum Insel Hombroich and Langen Foundation close to Düsseldorf, Germany. Insel Hombroich is a fascinating combination of a park, landscape art and a museum collection. The park, with a nice balance between human interaction and natural habitat, features ten relatively small buildings where artworks are presented. In addition to East Asian art and a storehouse of archaeological artefacts, the 20th Century works vary from lesser-known German artists to Hans Arp, Kurt Schwitters, Alexander Calder and Yves Klein.

As you walk through the park, from building to building (often constructed as walk-through), you become curious what might be on display in the next building. At the same time, on the way in-between these houses, you find yourself in different natural environments, forest-like parts to crossing a river on a small wooden bridge or open meadows. These small walks create a nice flow of observing, reflecting and anticipating both art and nature.

There is even more. At walking distance from Insel Hombroich, you’ll find the Langen Foundation, another private museum. A building out of concrete, steel and glass by the hand of the Japanese architect Tadao Ando was constructed to display parts of another private collection. It is situated on a former NATO base, a so-called ‘Raketenstation’ (a missile base from the Cold War) of which some elements are still visible in the part surrounding the Langen Foundation. The museum hosts temporary exhibitions and also displays part of the Langen-family’s private collection. But the most surprising artwork is the building itself, on one side surrounded by water, on the other side by grass; one part with a glass outside taking its place in the environment, another part of concrete delved into the ground – a bunker for art, but one with light enlightening the spaces. It feels like a building you can breathe in, but not touch; a building that forms both a recluse from the outside world and at the same time clearly relates to it.

It is an inspiring place, and I’ll post some more more pictures in the weeks to come.

Everlasting music – 1 – The Blue Nile

Some music albums, songs, compositions become a part of you. They hit you the first time you listen to them, they invade you the following listening sessions, and finally you integrate them into your body and soul.

Some music will always be associated with a specific time, period and/or place. As many people, I have discs that are connected to friends who recommended them to me, with whom I attended a specific concert or because they handed me over a certain disc / lp / cassette (yes, cassette…). Travelling by car is also a perfect way to turn a disc into one that will always be connected with a certain trip. Or you connect the music with a certain mood or phase you were in. Afraid to always connect it to a certain mood, I waited several weeks to listen to Radiohead’s King of Limbs because the special “newspaper” edition arrived at my doorstep in a personally difficult period. Of course, trying to postpone it, did not erase the connection I had already made. And listening to Radiohead’s brand new A New Shaped Pool even reflects that fruitless attempt of five years ago… You can’t manipulate music’s echoes, nor play tricks on your own mind… Much other music luckily has positive connections…

I am planning to expand different examples in future posts. As a start, I want to share an example how sometimes these musical fellows pop up at unexpected times and places. Finishing the first paragraph of this post with the words ‘body and soul’ imediately made me think of a marvellous album of The Blue Nile, Peace at Last.

The short description of the band on Allmusic reads as follows:

Scottish trio whose spare, sophisticated pop and plaintive vocals made for compelling listening, despite an infrequent release schedule.

I couldn’t do any better – I would only leave out the remark of the infrequent release schedule because I prefer quality over quantity. Four albums in twenty years is of course commercial suicide, but that does not make me love their music less… The album Peace at Last came out in 1996 when I was a student – and those times were mostly pre-internet. You had to buy the album to hear it – or copy it (on tape, of course) from a friend.

It is sonically their most relaxed record, and the songs sound like a glimpse into the soul of Paul Buchanan, the singer. The song Body and Soul is a nice example of restrained hope. The damped strumming of the chords, the strings that do not accomplish the height they are reaching for, their long notes replaced at other moments with short nearly staccato ones. But at the end of the song, the riff gets its own hopeful voice on electric guitar.

I also remember that, to be aware of concerts in other cities, you had to scroll every month through a calendar in a free music magazine (RifRaf, still alive today! Thank you for giving me so many hints in my early music-loving years!). Being printed in very small fonts, you were never sure if you missed something or not. But The Blue Nile nearly never played any concerts, so my hopes were not very high – and destroyed one morning when reading a positive review of a concert. They had played the evening before at Botanique in Brussels, 30 km from where I studied… Damn. I never got the occasion again… I’ll have to settle with some live fragments on Youtube, like this performance in ‘Later with Jools Holland’.

Kieslowski’s Decalogue: the Gaze as Encounter

The central characters in Kieslowski’s Decalogue are mostly lonely people. Most of them suffer a deprivation of identity, since identity is mostly formed in relation to the other. Their isolation creates a relatively silent film series in which dialogues are sparse. One of the key elements Kieslowski uses to symbolise the attempts for contact with someone else, is the gaze.

This can be the gaze towards something, or the gaze towards someone. In the Decalogue, as in other films by Kieslowski, objects are frequently presented in close-ups to symbolize key moments. Moments in which the characters recognise that something has an impact on them – an impact that can be both good or bad.

In Decalogue 2 for example, water dripping from a pipe is used two times.

In the first half of the film, we see and hear dripping water on a metal pipe or the frame of a bed, and suppose it is in the hospital room of Andrzej, the sick man whose wife is pregnant from another lover. There is no clear location defined for the dripping water – even if the film cuts to Andrzej in bed, fighting against fever, feverish sweat on his head, we are not sure it is in one and the same room. He directs his gaze in a certain direction, but we don’t get a confirmation that he is actually looking at the dripping water.

Because we are not sure if both Andrej and the dripping water are in one and the same room, we are stimulated to read the dripping water not (or not merely) as a sign of decay of the hospital, but as a sign of decay of Andrej.

The same effect applies when after a close-up of Andrej’s face, the film cuts to water dripping over crackled plaster on a wall. The third time we see the water dripping on or close to the leaves of a plant – which is the only spatial link: these are supposed to be the leaves that his wife peeled off a plant. However, this plant was standing on the window-sill at their apartment, not in the hospital room. We could read this as a sign that potential loss is not only threatening Andrej, but his wife too, since she plans on aborting the child she carries if her man is expected to survive.

The same dripping water is used another time near the end of the film.

This time however his wife is present, and the location is revealed to be the hospital room. However, there are two important changes. Andrej is not alone in the room, fighting against his fever, but his wife is caressing his head, trying to help him. And this time the flow of the water is not presented as something infiltrating the walls, but it is collected in a reservoir. Since the location is now clear to us, the close up of the drops in the socket also make us think of intravenous therapy, where liquid substances with medication are brought into the veins. Are we looking at a partial cure?

This kind of symbolic objects, often connected to characters by their gaze, are abundant in the Decalogue. They not only often symbolize a change or a potential shift, but because their role is not always explicit, they also enforce implicit interpretation – which encouraged other people to say that these objects in Kieslowski’s films often have the tendency to “look back” at the character. These objects often resonate and change perspective, in themselves, as well as for the characters. In the words of Vivan Sobchack: these are “key moments of reflexive awareness”.

In a lecture at Cinema Zuid in Antwerp this Friday, I will also focus on the gaze between people in the Decalogue, how Kieslowski often shows us the gaze of people through reflections and framings, and how direct gazes between people are also used to show the evolution these people go through.

Welcoming colors

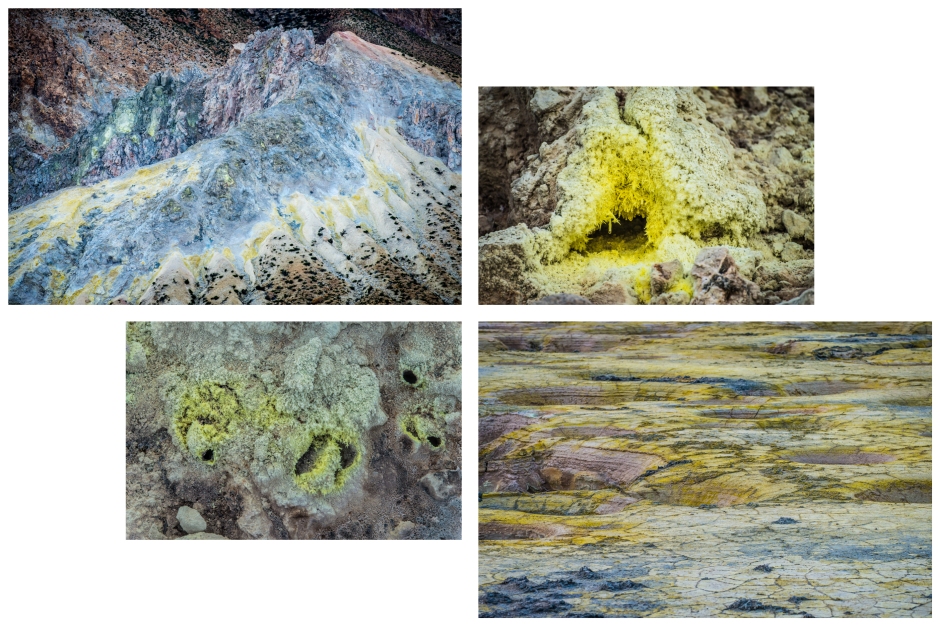

Summer textures on a volcanic Greek island

Parajanov art collages in Brussels

Marvel continues. The remembrance of the Armenian genocide (1915) inspired the Boghossian Foundation to bring a selection of collages by Sergei Parajanov to Brussels. Parajanov is most known for his exceptional films Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964), a personal blend of folklore, color and vision, and the stunning Sayat Nova (The Color of Pomegranates, 1969), a tableau-like celebration of the Armenian poet Sayat Nova.

Sayat Nova

Sayat Nova

The films being too experimental for the social-realist paradigm of the USSR, and Parajanov expressing a critical voice as well as being openly gay resulted de facto in a ban on filming for about 15 years, and years of imprisonment in a labor camp. In this period, Parajanov started to work on paper collages, to create ‘mini-films’. He also made lots of three-dimensional cabinets and boxes. His film shots already often combined several layers into one image, but his collages thicken this multiplying effect and combining of several influences, spheres, colors or significations. James Steffen, who published the first English-language study on Parajanov’s films, wrote a nice introduction for the catalogue of a similar exhibition in 2014 in New York.

The exhibition, with a selection of artworks from the Parajanov-museum in Armenia’s capital Yerevan, takes place in the magnificent Art Deco villa Empain from September 24 to January 24 2016.

Villa Empain